PART III: HOW TO RESTORE BELIEF IN GOVERNMENT BY EQUIPPING REFORMERS TO DELIVER RESULTS

Public dollars have the power to change lives. Used well, with attention to results, these dollars can catalyze progress toward solving America’s biggest challenges at scale. In 2018, across federal, state, and local governments, the public sector spent well over $2 trillion on social services and social programs—more than five times the amount raised from individuals, foundations, and corporations across the entire philanthropic sector in the United States. While other sectors are also needed, they can’t come close to the power of government when it comes to scaling what works to achieve better outcomes for the millions of families poorly served by the status quo.

We see tremendous opportunities for the social entrepreneurs and systems innovators across the America Forward Coalition to partner with government agencies to rebuild and strengthen our social safety net and provide more effective and inclusive systems to unlock the productive potential of all people.

Unfortunately, we have a long way to go before this vision becomes reality.

BARRIERS TO RESULTS, INNOVATION, & PARTNERSHIP

Most government programs are designed to address a narrow problem without taking into account its root causes and connections to other challenges. And only a small fraction of government programs are tied to measurements, so much of public funding isn’t linked in any way to demonstrable results. To make matters worse, government agencies spend only about half of their time working on mission-related performance. They spend the other half complying with oversight requirements, at a great cost to taxpayers. Given this reality, it is not surprising that government agencies are disinclined to try new approaches, and they may even be penalized for trying to innovate.

Because of the rigidity in many public programs, social entrepreneurs trying to scale proven solutions through government partnerships are often stymied. Innovative programs rarely fit well into a public funding stream. Or if there is a funding stream, it is off limits because the law designates another type of provider or another intervention strategy. Or it covers only a small part of the services, or pays only a portion of the cost. Or the process for securing the funding is complicated and burdensome, beyond the expertise and capacity of most nonprofit staff.

If innovators apply anyway and are successful, they may find that they have to change what they are doing or who they are serving, and that government oversight focuses on adherence to a complex set of reporting rules emphasizing inputs rather than outcomes and results. They may well choose to forgo future government opportunities altogether and continue to operate at the level of scale other revenue sources allow.

While most public servants are motivated by mission, they may also be limited by their own experience. With a seniority-driven personnel system designed in the 1940s, the federal government has a workforce whose average age is nearly 50, and an average employee tenure of 15 years—nearly four times the average of the broader workforce. Less than 6% of senior executives at federal agencies were hired from outside the federal government, while over 68% were hired from within the same agency subcomponent. Because so few people move in and out of government, many people administering programs don’t have work experience in other sectors, or lived experience with the issue they are addressing, thus depriving the agencies charged with solving a problem of important sources of knowledge.

The disconnect between our government and the communities it serves becomes even more jarring when we turn to our elected representatives. While every year the number of people of color and women increases among elected officials, they are still significantly underrepresented relative to their population at every level of government. So, too, are young people: Over the past 30 years, the average age of a member of Congress has increased with almost every new session; today, the average age of a representative is 57, and the average age of a senator is 61. People from less-advantaged backgrounds, however, make up the most profoundly underrepresented group; they account for just 4% of elected officials, even as millionaires, for the first time, make up a majority of Congress. As a result, the essential voices of the people who are deeply affected by policies aimed at reducing poverty and inequality are effectively absent from the halls of power where our priorities and policies are determined.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

We call on all policymakers, social entrepreneurs, change agents, and ordinary citizens to lift our sights beyond our narrow programmatic interests and unite to make democracy, and government, focus on results and work better for everyone.

OUR GOAL

We aim to reduce poverty and inequity by making government programs and partnerships efficient, effective, and easy to access, with measurable results.

WHO WE ARE

Organizations in the America Forward Coalition work closely with government and community partners to get better outcomes by breaking down silos, improving learning, reducing poverty, and building the modern social-sector workforce our country needs. We use new tools, such as Pay for Success projects and other outcomes-based approaches, to drive resources to providers who can get more powerful results. And we work to ensure that the voices of people closest to the problems are heard, and their expertise heeded.

WHY WE CARE

With the magnitude of challenges we face as a nation, we can’t afford to waste public dollars. Government has the power to change lives with the right people and partnerships, appropriate resources, the flexibility to innovate, and the ability to link funding to outcomes and reward results.

THE PROBLEM

We can’t make good on the idea that all people can succeed regardless of where they start without government playing a constructive role. That means setting the right priorities and making sure that every tax dollar delivers results. But the complex set of government programs designed to address inequity and fight poverty in America has, to date, not made sufficient progress toward this end for a variety of reasons.

THE SOLUTION

Redesign government programs to focus on results and improve outcomes.

We can’t make good on the idea that all people can succeed regardless of where they start without government playing a constructive role. However, too often government programs lock problems in place.

Programs focus on compliance, not outcomes.

Without specific measurable goals and a way to track progress toward them, we can’t innovate or build evidence. Although many sources of data are available that would enable agencies and providers to measure impact, too little has been done to make that data usable and accessible to support outcomes measurement. Instead of developing an outcomes-oriented infrastructure, most government programs remain focused on compliance. Complex, detailed rules make it hard for organizations to operate programs, and thereby limit participation of new providers, including grassroots organizations that are most proximate to the population served.

Programs don’t embrace the expertise of people closest to the problems they are trying to solve.

Unfortunately, the misguided idea that people are poor because they don’t want to work or can’t make good decisions is deeply embedded in the design of many government programs. Examples include work requirements in public assistance programs that fail to address the needs of individuals unable to work, and limitations in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) that support the purchase of certain types of food, but not others such as prepared or hot foods. Rather than value the expertise of people who have lived in poverty, policymakers too often substitute their own judgments for those of the people they hope to help. In contrast, successful businesses know it is important to hear from customers when they design products and services. In fact, more than 600,000 people are employed in market research—an industry growing by 20% a year. But while elected officials spend money on polling to learn how to appeal to voters, policymakers rarely design solutions with the people they are trying to help at the table. The resulting programs, while well intentioned, don’t always help the people they are designed to serve and sometimes lead to unforeseen consequences.

In addition, too often government funding is channeled to a set of incumbent providers that have established relationships with the agency overseeing the program, not necessarily providers with the best potential for success. Alternative providers closer to the community, as well as nonprofit organizations that could help traditional providers improve, operate outside the system, largely depending on philanthropic funding, which is unevenly distributed across communities.

Programs support single-point solutions for multifaceted problems.

Often individual government programs are deployed to address discrete needs of individuals living in poverty, even though families are likely to experience multiple, interrelated challenges. Rather than building on the assets of these families, helping them in a holistic way, and addressing the larger ecosystem in the community that reinforces and exacerbates challenges, many government programs treat individual symptoms based on the jurisdiction of the executive branch agency and Congressional committees that created them. They provide housing supports, food vouchers, health care, child care, English language classes, legal services, job training, education, and other assistance through individual, uncoordinated rule-bound programs, all of which operate independently. Families navigating through this morass may get some of the help they need to survive, but likely not the kind of support they would choose if they could determine their own paths to change their circumstances.

The same is true of communities where poverty persists. Rather than transform the ecosystem, it’s more common for government programs to direct resources to specific providers that map to the agency of government offering the assistance rather than incentivizing the development of a strong community-based system of supports. Imagine how much more robust and effective our social safety net might be if these programs worked seamlessly and holistically together, interacting with each other to create a sustainable ladder into the middle class, rather than the disjointed and fractured maze that families and social entrepreneurs alike find so challenging to navigate.

Programs face challenges that limit their ability to learn and innovate.

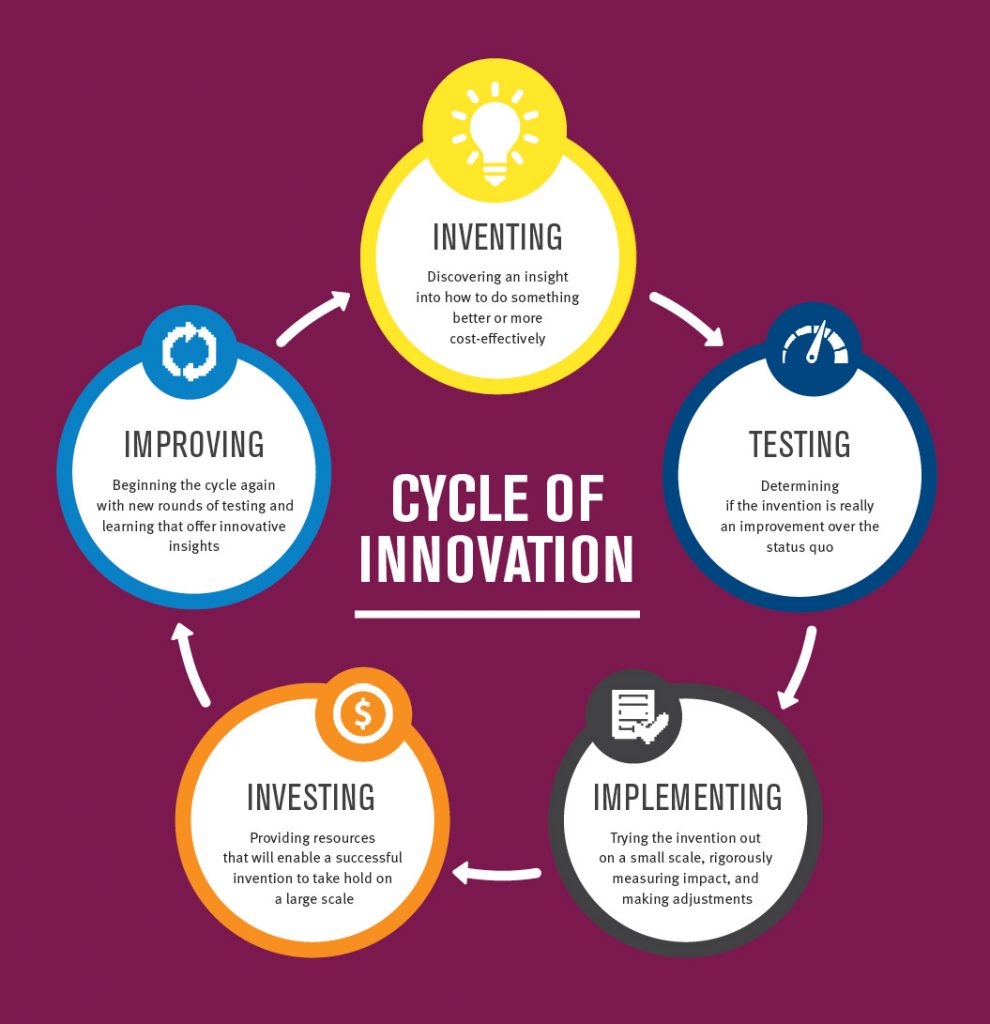

We are in the process of building a growing and evolving body of evidence about what works well. In many businesses and organizations outside of government, an innovation cycle supported by experimentation and data analytics drives improvement. Unfortunately, no such system exists at scale within the parts of government charged with solving the most intractable problems associated with poverty.

Nor is it the norm for one part of government to work with or learn from another—even if they are trying to serve the same people. The processes associated with government programs—passing legislation and issuing regulations and formal policies—move slowly in a gridlocked and partisan climate and are so rarely updated that discredited practices may actually be frozen in place for decades.

Agencies may be prone to issuing informal rules and conforming to operating norms that are hard to challenge, even by the people who work in them. In an article published in 2018, professor Jeffrey Liebman, director of Harvard’s Government Performance Lab, identified two main obstacles that prevent state and local government agencies from more successfully scaling approaches that measurably move key outcomes: “First, many agencies lack leadership with a time horizon that is sufficiently long to prompt performance improvement projects, that is philosophically oriented toward using data to drive change, and that is willing to bear the stresses associated with driving change. Second, many agencies lack staff with the combination of spare capacity, expertise, and desire necessary to lead data-driven reform projects.”¹

Operating in similarly constrained systems, just 60% of federal employees report they feel encouraged to come up with new and better ways to do their jobs, a substantial 16 points behind the private sector. All of this might in part explain why in 2015, just 20% of the public believed the federal government is run well, and 59% believed government needed “major reforms,” a 22-point increase over the past two decades. Far too many public employees at all levels of government serve in systems that do not encourage or incentivize unlocking of creativity, inspire innovation, and encourage data-driven performance management.

THE SOLUTION

In large part because of the pathbreaking work of America Forward Coalition members, we have learned a great deal in recent years about how to redesign government programs to focus on and improve outcomes.

By using evaluations and data to track what works, we can build evidence and actively manage performance to get better outcomes. By sharing de-identified data with community providers, we can empower them to get better results for the families they serve. We can drive greater resources toward what works best, while modifying and adapting those approaches as needed based on the unique customized needs of individual families and local communities. By enabling those closest to the people served to assemble benefits and services in ways that are easy to understand and access, we can achieve better results. And by recruiting a new generation of diverse talent to elected, appointed, and civil service positions, we can bring new perspectives and approaches to solving critical challenges.

To make it easier for organizations to manage government funds, we should strip away unnecessary program requirements that aren’t tied to results, while maintaining a critical focus on the most underserved and overlooked populations. Even better, we can acknowledge the larger ecosystem that affects outcomes, and call on public agencies to work in partnership with nonprofits and community-based organizations, as well as other government offices, business, and philanthropy.

One clear way to improve the status quo is to move to a new approach that ties public dollars to better outcomes. This shift critically alters the way government agencies think about programs, deemphasizing enrollment and requirement checklists, and focusing attention instead on whether lives actually improve.

One clear way to improve the status quo is to move to a new approach that ties public dollars to better outcomes. This shift critically alters the way government agencies think about programs, deemphasizing enrollment and requirement checklists, and focusing attention instead on whether lives actually improve.

A number of America Forward Coalition organizations are at the forefront of developing a new approach designed to achieve this shift, which we have already referenced, called Pay for Success (PFS). Pay for Success emphasizes innovation, prevention, and accurate data. It encompasses “PFS contracting,” in which payments are made (typically by the government) in part or entirely based on the achievement of measurable outcomes.

“Pay for Success financing” is a more specific related tool through which mission-driven investors, including philanthropies, fund services and are later repaid (usually by a government entity) through success payments if those services achieve key outcomes, as measured by an independent evaluator. This approach has sometimes been referred to as “social impact bonds.” Over the last decade, more than 25 pathbreaking state and local projects have launched in the United States using Pay for Success financing, pushing jurisdictions to tie public funds to measurable results and forging new partnerships among nonprofits, governments, philanthropy, investors, and evaluators.

While Pay for Success financing is an important tool that can and should continue to scale, it appears that the future of Pay for Success work is not primarily focused on engaging external investors. In fact, a growing cohort of Pay for Success projects features no external investors at all, and several of our Coalition members are scaling Pay for Success approaches across entire agencies and systems to rebuild our fraying social safety net without necessitating Pay for Success financing. We can and should continue to harness the catalytic potential of the financing model, in concert with foundations, impact investors, and other funders. But almost all of the policies we propose in this book do not depend on the financing model, or on partnering with external investors.

Third Sector is a strong example of an America Forward Coalition member that has broken new ground helping state and local jurisdictions across the country develop outcomes-driven initiatives, using integrated data and active performance management of contracts to deliver better results for families and build a stronger social safety net. In Santa Clara County, California, for example, Third Sector worked with local providers to fund mental health supports and other wraparound services through an outcomes-based contract. The county committed to make outcomes payments to providers if an evaluation found those served are ultimately healthier and make fewer trips to emergency rooms, psychiatric facilities, or jails over a six-year period.

On a larger scale, Third Sector is helping Washington State’s Department of Children, Youth, and Families to tie nearly $1 billion in biennial funding across over 1,000 contracts for child and family services to improved outcomes and quality standards, a paradigm shift that puts the needs of clients and communities at the center of its contracting structure. Over the past year, Third Sector has engaged in conversations across the federal government about ways to implement outcomes-oriented approaches to federal funding streams, such as TANF and SNAP. Through these discussions, federal agencies are beginning to reimagine how dollars can be deployed to achieve measurable outcomes.

Social Finance is another America Forward Coalition member driving the outcomes-based funding movement forward in partnership with government agencies. For example, Social Finance has helped develop “rate cards”—a menu of outcomes that government seeks to achieve and the prices they are willing to pay for each outcome achievement. They are used as a procurement and contracting tool with the ability to standardize Pay for Success financing and drastically reduce the time such deals take to get to market. One rate card can result in multiple contracts with multiple providers that must deliver against predetermined outcomes and prices, receiving payment only when the stated outcomes are achieved and participants’ lives are positively impacted. Using this approach, Social Finance recently helped structure and launch a new project in which Connecticut’s Office of Early Childhood agreed to pay bonus payments to a cohort of early childhood home-visiting providers serving families who subsequently benefit from improved birth, health, child safety, and economic security outcomes.

Social Finance is also at the forefront of leveraging federal dollars to scale Pay for Success financing. It helped to structure projects spanning jurisdictions from New York City to Anchorage, Alaska, for the first federal Pay for Success competition, the Social Impact Partnership to Pay for Results Act (SIPPRA) program. Social Finance also helped scale a promising new intervention called the Accelerated Study in Associate Programs, an intensive set of financial, counseling, and wraparound supports for community college students in Lorain County, Ohio, by leveraging a new state-level funding stream in Ohio tied to improved graduation rates. Based on a rigorous evaluation, the project appears to be on track to double three-year graduation rates for students served, compared to the status quo. Finally, Social Finance is at the forefront of deploying a promising new outcomes-based tool—income-sharing agreements—through which impact investors fund targeted training and post-secondary education programs, and are subsequently repaid based on a modest share of a student’s future income, if the student earns above a minimum salary threshold.

Many America Forward Coalition members are doing the hard but vital work of partnering with evaluators and the public sector to leverage administrative data to build evidence for the effectiveness of their services. These examples span numerous domains and areas of focus, including KIPP for K-12 education; Bottom Line, uAspire, College Forward, and Braven for higher education; Roca for criminal justice; YouthBuild and Year Up for opportunity youth; Per Scholas for workforce development; the Corporation for Supportive Housing for combatting homelessness; and AppleTree for early learning. By looking rigorously at outcomes, pursuing evaluations to measure what works, and constantly seeking to build evidence, these and many other members of the America Forward Coalition are demonstrating that social entrepreneurs and nonprofits across America can partner with government to measurably improve the lives of the people they serve.

To use data effectively, implement Pay for Success, or integrate technology effectively requires expertise not always present in public agencies. America Forward Coalition members are tackling this challenge in a variety of ways.

For example, FUSE Corps takes on the talent challenge by partnering with cities and counties on a range of issues, including economic and workforce development, health care, public safety, climate change, and education. FUSE Corps works closely with its government partners to design yearlong strategic projects, recruit experienced leaders to become fellows who will take on those challenges, and provide ongoing support to help fellows achieve their full potential for community impact. By helping to craft new policy, roll out new public services, and improve existing programs, FUSE Corps governments work better for the people they serve. Since 2012, FUSE Corps has placed more than 140 fellows in over 80 local government agencies throughout the country. More than 50% of alums have continued to work in roles in civic leadership after their fellowships, and 90% of partner government agencies have returned each year with requests to host additional fellows.

Other America Forward Coalition members focus on ensuring that the views and voices of underrepresented people are heard by policymakers. For example, POWER is an interfaith organization representing over 50 congregations throughout Southeastern and Central Pennsylvania; it organizes people to work together to transform the conditions of their neighborhood. In the spring of 2011, more than 150 lay and clergy leaders from POWER congregations conducted 40 research meetings with public- and private-sector leaders to gain an understanding of how and why key systems were failing to provide the pathways to opportunity that families need. POWER leaders then held a Founding Convention, bringing together 2,000 congregational members, allies, and city officials to affirm a change agenda. Representing the coming together of dozens of congregations from across the city—across lines of race, income level, neighborhood, and faith tradition—to build broad-based power for policy change, POWER secured commitments from public- and private-sector leaders to work toward a vision of connecting 10,000 low-income Philadelphians with living-wage jobs.

These organizations, and others like them, show us the way. They work with government to improve outcomes by:

- Focusing on results over compliance

- Accessing administrative data to measure long-term effectiveness

- Silo-busting, enabling individuals to receive comprehensive, personalized services

- Building a sustainable pipeline of talent to foster innovation and enable outcomes-based approaches to scale

- Leveraging evaluations and technical assistance to improve the efficacy of services and programs over time

- Receiving and incorporating constant feedback from those closest to the problem, enabling continuous learning, improvement, and innovation

The impact of these strategies underscores the importance of opening more funding streams to support the nonprofits that can help government and providers alike.

POLICY PROPOSALS

28. APPOINT LEADERS FOR INNOVATION AND INCLUSION IN THE EXECUTIVE BRANCH.

Ensure that the White House, as well as every governor, has a chief social innovation officer to lead efforts to improve government through social innovation.

Changing the long-standing practices of government requires the active leadership of the chief executive. Creating a new White House Office of Innovation, Outcomes, and Engagement, led by a chief innovation officer reporting directly to the president, with the authority both to help set budgetary priorities through the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and to convene and direct policy through the Domestic Policy Council, will vastly increase the odds that efforts to promote innovation across government will succeed. Ideally, the chief innovation officer will play a coordinating role with agency heads and other senior officials. Innovation office staff with working knowledge of government, business, and the nonprofit sector will bring the perspectives necessary to make government work better for everyone. A similar office should be established in every major executive branch agency and replicated at the state and local levels. These offices should play a leadership role in five areas:

Changing the long-standing practices of government requires the active leadership of the chief executive. Creating a new White House Office of Innovation, Outcomes, and Engagement, led by a chief innovation officer reporting directly to the president, with the authority both to help set budgetary priorities through the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and to convene and direct policy through the Domestic Policy Council, will vastly increase the odds that efforts to promote innovation across government will succeed. Ideally, the chief innovation officer will play a coordinating role with agency heads and other senior officials. Innovation office staff with working knowledge of government, business, and the nonprofit sector will bring the perspectives necessary to make government work better for everyone. A similar office should be established in every major executive branch agency and replicated at the state and local levels. These offices should play a leadership role in five areas:

1. Facilitate Pay for Success efforts.

Implementing Pay for Success principles takes expertise and coordination. Working with OMB at the federal level, the federal Innovation Office would coordinate and align federal programs and funding streams to ensure guidance and regulations are more user-friendly to states, local government, and providers pursuing Pay for Success; make it easier to utilize federal dollars for outcomes payments; and help ensure agencies do not stymie the implementation of Pay for Success programs. The office would release national guidance on evaluation and data-sharing (including with providers), and restructure federal funds to make the federal regulatory frameworks governing them less disjointed; spread best practices and serve as a central repository of model documents to streamline the Pay for Success development process; and convene federal, state, local, and nonprofit partners to break down silos, and collaborate on multifaceted projects that drive toward solutions. This office would work to make the federal government catalyze rather than obstruct outcomes-based projects. A similar role would be played at the state level, in partnership with state budget offices and agencies.

2. Champion talent strategies.

The chief innovation officer would lead a campaign to call a new generation of diverse talent to public service. Traditional hiring pipelines don’t necessarily produce a talent pool that is inclusive of a diverse range of expertise, including technology, cross-sector partnerships, and the expertise developed through lived experience in low-income communities. The Innovation Office would work closely with the Office of Personnel Management (or relevant state agency) to track data regarding recruitment, hiring, and retention, and take charge of coordinating a range of strategies across government, including national service, midcareer programs, and professional development strategies for existing employees.

3. Dismantle barriers to equity across government.

The Innovation Office should explicitly prioritize equity, with the goal of seeding and funding more outcomes-based projects that reduce racial disparities, ensuring that all talent strategies have equity at their core, and make equity central to all place-based and cross-sector strategies. It should develop a philanthropic index to identify areas poorly served by philanthropy that should be automatically exempted from the requirement for matching funds in government programs. As part of this process, it should review and make recommendations to update long-standing formulas and practices that disadvantage underrepresented communities. It should also review and address government regulations and practices that inappropriately exclude individuals with criminal histories from participating in work, education, or our democracy. And it should help ensure that affected individuals, families, communities, and local nonprofits have direct and continuous input into how programs are designed.

4. Coordinate place-based initiatives.

Numerous place-based initiatives operate across government with little coordination. The Office of Innovation would coordinate these efforts, with the goal of making it easier for communities to participate in multiple initiatives and increasing their likelihood of achieving positive impact.

5. Develop cross-sector partnerships.

Every challenge that government seeks to address is impacted by other sectors, including business, nonprofits, and philanthropy. Working collaboratively with external partners concerned with education, employment, equity, and other issues will greatly increase the potential for impact. This effort should be led by the Office of Innovation to ensure coordination across government.

29. VALUE THE EXPERTISE OF UNDERREPRESENTED PEOPLE.

Unless the people whose lives are impacted by government programs are included, heard, and respected, important insights will be missed, making programs less successful.

The people whose lives most depend on effective government policies—especially young, low-income people—have the least voice in policy. At every level of government, and in every branch, opportunities exist to benefit from their expertise, whether through advisory councils, focus groups, or incorporating design thinking into program design. Every office and agency can host paid fellows who have lived experience with the challenges that the policy is intended to address, and ensure that their hiring and personnel processes operate with attention to diversity, equity, and inclusion. In addition, policymakers can support reforms to reduce the influence of money in politics, make it possible for people to run for office without engaging in excessive fundraising, and mentor candidates from underrepresented groups.

30. INCORPORATE OUTCOME-BASED FUNDING IN EVERY PROGRAM.

Incorporate performance-based payments that are contingent on achieving measurable outcomes, not complying with rules or counting the number of people served, in every major formula and discretionary

grant program.

Pay for Success seeks to transform how governments partner with communities and direct dollars with a human-centered, equity-driven lens. Projects have built evidence for supportive housing, home visiting, behavioral health, and many other examples, while underscoring the need for data-driven government, outcomes-driven contracts, performance management, program evaluation, cross-sector partnerships, and other approaches. Pay for Success and outcomes-based approaches can empower communities to strengthen their social safety nets, and align policy and services to ensure, as our workforce rapidly evolves, that upward economic mobility keeps up with the relentless pace of technological change.

Over the last decade, the America Forward Coalition, in partnership with other advocates for outcomes-based funding, has worked to make over $1.7 billion in annual federal funding available for Pay for Success and other outcomes-based models. We have also seen firsthand the challenges presented by the lack of an “outcomes infrastructure” at all levels of government. These include underdeveloped data systems, barriers to data-sharing and integration, insufficient staff to execute Pay for Success projects and evaluations, limited support for most nonprofits and service providers to scale evidence-based services, as well as an acute funding shortage to address these collective challenges. The high complexity of Pay for Success projects, greatly exacerbated by the lack of “outcomes infrastructure” that can allow an outcomes-based approach to thrive, has imposed considerable burdens on nonprofits, providers, and local governments. Further, aligning incentives across the provider, government payer, and investors can pose additional challenges.

These challenges are further exacerbated by the insistence on utilizing only “rigorously proven” services, leaving out many nonprofits, perspectives, and opportunities for evidence building in partnership with communities. Many grassroots organizations close to the people served don’t have the resources to pursue rigorous evaluations, even if they achieve powerful results. They may have ethical concerns about denying help to people in order to carry out evaluations that require sorting prospective clients into a treatment group and a control group. The Pay for Success field also has far too few funders, policymakers, and program leaders of color. As a result, the leaders who dominate the current field too often collectively deploy capital in under-resourced communities and make critical decisions without including diverse voices proximate to these communities.

To go to the next level of outcomes-based funding, we must address these many challenges. Government can help build the necessary “outcomes infrastructure” by investing in staff, technical assistance, evaluations, data systems, and other support for social entrepreneurs and state and local governments.

To go to the next level of outcomes-based funding, we must address these many challenges. Government can help build the necessary “outcomes infrastructure” by investing in staff, technical assistance, evaluations, data systems, and other support for social entrepreneurs and state and local governments.

To make it possible for every major formula and discretionary grant program to more effectively help the individuals they are intended to serve, we should:

- Allow funding flexibility, embedded systemically across federal programs, grants, and funding streams, to empower state and local governments to support better data-systems, hire staff, pay for technical assistance, and fund evaluations to create conditions more conducive to outcomes-based payment models.

- Improve data infrastructure, including:

- Developing short-term “proxy” measures tied to long-term outcomes (e.g., credits accumulated for disadvantaged college students, “adherence measures” for juvenile justice prevention, “days in stable housing” for supportive housing for homeless adults) to make it possible to incorporate short-term success payments.

- Funding technical assistance and staff support so more jurisdictions will be able to bring their data systems into the modern age, making anonymized administrative data available to the social sector in real time, with strong privacy safeguards. This funding should be partly conditional on using the data to develop new outcomes-based payment models, and on recipients sharing scrubbed data with the community at large. This in turn will enable and encourage nonprofits and governments alike to actively manage their performance and track outcomes at the population level, enabling policymakers to make exponentially more data-informed policy and program decisions than is generally possible today.

- Identify low-cost alternatives to randomized control trials to make it possible for more organizations to develop an evidence base that will open doors for more funding.

- Release federal guidance to focus audits more on outcomes and less on compliance. Audits serve an important purpose in reviewing the financial, programmatic, operational, and management systems and procedures of government to assess whether the agency is operating efficiently. They are driven by a need to conform to a prescriptive compliance framework focused on risk mitigation and financial accountability. And, while audit guidelines generally refer to outcomes, they do not provide guidance on outcomes measurement or reporting. Outcomes audits would instead incorporate a review of an agency’s grantee evidence of program or intervention outcomes. This approach to auditing would still ensure the financial integrity and efficient use of resources, and it would also more clearly articulate what is being accomplished with the money being allocated.

- Set aside a percentage of major funding streams for innovation and learning. Every major formula and discretionary grant program should incorporate a minimum percentage to support innovation and learning at the federal level as well as the grantee level, spurring state and local agencies and nonprofit grantees to take bolder steps to innovate and evaluate their programs. These funds would support evaluation, data sharing systems, training and technical assistance, demonstration programs, and other activities that tell us what works and spread that knowledge to improve outcomes.

- Build community nonprofit evidence capacity. Make grant funding available for local community nonprofits and providers to build evidence of

their effectiveness. - Require and incentivize Equity Impact Assessments: Just as a major public works project requires an environmental impact statement, recipients of major federal grant dollars should submit equity impact assessments, reporting out current status quo key outcomes for individuals served, broken out by race and gender, and map out a strategy for increasing equity, including more effectively engaging leaders with relevant lived experience. The federal government should also pilot incentive grants for communities that measurably increase equity.

31. LAUNCH OUTCOMES-BASED PROJECTS AT THE STATE AND LOCAL LEVELS.

Improve health, education, employment, and other outcomes for low-income people by developing new models that combine funding streams and tie payments to results.

The policies proposed above can help improve outcomes for families across this country and help Pay for Success scale. At the same time, policy action in Washington, DC, while critical, is not sufficient. We need bold new leaders at the state and local levels to work together to put this new vision for outcomes-based work into practice. And we need not wait for Washington, DC, to act.

A bipartisan cohort of governors, local officials, and service providers should partner together to launch a new cluster of Pay for Success projects. Unlike the first generation of projects, which often leveraged Pay for Success financing with support from external investors, these projects need not necessarily incorporate this element. Instead, new projects could leverage a mix of Pay for Success approaches, including outcomes-based payments, improved integrated data, commingled federal funding streams, and innovative partnerships with philanthropy. They could engage the talents of a new cluster of staffers who excel at leveraging administrative data to more effectively manage public contracts based on performance and results. And governors and mayors could commit to scaling these approaches in their budgets if, based on a strong evaluation, they exceeded key outcomes targets.

A bipartisan cohort of governors, local officials, and service providers should partner together to launch a new cluster of Pay for Success projects. Unlike the first generation of projects, which often leveraged Pay for Success financing with support from external investors, these projects need not necessarily incorporate this element. Instead, new projects could leverage a mix of Pay for Success approaches, including outcomes-based payments, improved integrated data, commingled federal funding streams, and innovative partnerships with philanthropy. They could engage the talents of a new cluster of staffers who excel at leveraging administrative data to more effectively manage public contracts based on performance and results. And governors and mayors could commit to scaling these approaches in their budgets if, based on a strong evaluation, they exceeded key outcomes targets.

If governors and other local leaders seize this opportunity, a new cohort of outcomes-based projects could accomplish critical objectives, including:

- Achieving scale and decreasing average project launch costs. Launching just one project can be complex, requiring staff, technical assistance, structuring, and data support—all of which can be challenging for a single state to easily absorb. Seeding projects across multiple sites could enable intermediaries, policy experts, lawyers, and funders to serve multiple projects at once.

- Help achieve federal policy change. Governors and other policymakers working together across the aisle could better secure federal support and policy reforms from Washington, DC. Engaging key federal allies early in the process could also make local officials bolder about pursuing imaginative and innovative new approaches in their communities.

- Engage new partners and catalyze new funding. Communities participating in this effort could partner with health care stakeholders and develop new approaches to leverage Medicaid dollars to fund effective prevention strategies such as permanent supportive housing. A multistate cohort could innovate across a range of other promising areas, including higher education, workforce development, and “dual-generation” initiatives that simultaneously support the needs of parents and young children in or near poverty.

32. SUPPORT “SOCIAL INNOVATION ZONES.”

Building on existing place-based and results-focused efforts, provide funding for governor-designated zones of high and persistent poverty, combined with expert technical assistance and waivers to pool federal funding with fewer restrictions, based on a community-designed plan.

Over the last half century, place-based “zone” programs have been implemented to aid communities experiencing persistent poverty. Some have focused on physical infrastructure or coordinated service delivery, while others have taken a market approach, seeking to incentivize investment on the theory that economic interventions can drive change.

Most place-based initiatives focus on a neighborhood or other well-defined location over a period of years, offering a comprehensive array of strategies to improve lives as measured by various socio-economic indicators, such as affordable housing, social services, small business assistance, educational reform, and workforce development. These place-based initiatives, whether undertaken by the philanthropic or public sector, tend to require a single nonprofit service organization or community development corporation to act as “lead agency,” coordinating other organizations to work toward common outcomes. They sometimes blend economic development and human service strategies. And they often call for resident empowerment and cross-sector collaboration involving government, business, nonprofits, and civic associations.

Performance Partnerships make it possible, in communities where there are multiple initiatives overlapping in the same geographic area, to pool resources across government agencies if doing so will lead to better outcomes for at-risk youth. The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2014 authorized the establishment of up to 10 “Performance Partnership Pilots,” each of which is represented by a coordinating body comprised of the nonprofit agencies and other partners engaged in the overlapping initiatives. The Departments of Education, Labor, and Health and Human Services, and the Corporation for National and Community Service permit pilot sites to seek waivers of specific program requirements that inadvertently hamper effective services for youth, as well as pool a portion of their funds for unrestricted use. Subsequent annual appropriations bills enacted in 2015 and 2016 expanded the list of participating federal agencies to include the Departments of Justice and Housing and Urban Development. In exchange for flexibility, the selected jurisdictions are held accountable for a higher level of performance in meeting a set of hard, measurable outcomes.

In recent years, a set of Pay for Success pilots as well as Performance Partnerships have taken place-based strategies to a new level by tying funding to outcomes and loosening restrictions on public dollars. Our Social Innovation Zone strategy would combine both of these approaches to make scalable both place-based strategies and flexible, results-focused funding.

Through this initiative, governors would designate zones of persistent poverty, ideally building on existing place-based and results-focused efforts. These communities would receive waivers to pool federal funding with fewer restrictions, and use it, based on a community plan, to change outcomes for the whole population. Communities able to exceed a threshold share of their federal dollars in these zones explicitly tied to an outcome or set of outcomes would receive additional federal incentive dollars to further augment their service array in these zones, and would receive additional federal dollars to scale the approach if the services actually met or exceeded those target outcomes, as measured by validated administrative data.

The community plan would set specific measurable outcomes relating to upward mobility and well-being, along with strategies to achieve them. It would be developed with residents of the zone at the table as full partners, with businesses, higher education institutions, schools, and local government. Plans could flexibly combine relevant federal and state funding streams, consistent with safeguards to prevent the misuse of funds. Federal agencies would provide clear guidance to enable local officials to combine federal dollars, starting with the Social Services Block Grant, higher education and workforce programs, TANF, WIOA, Perkins V, Child Care Development Block Grant funds, and other mandatory spending based on local plans.

The community plan would set specific measurable outcomes relating to upward mobility and well-being, along with strategies to achieve them. It would be developed with residents of the zone at the table as full partners, with businesses, higher education institutions, schools, and local government. Plans could flexibly combine relevant federal and state funding streams, consistent with safeguards to prevent the misuse of funds. Federal agencies would provide clear guidance to enable local officials to combine federal dollars, starting with the Social Services Block Grant, higher education and workforce programs, TANF, WIOA, Perkins V, Child Care Development Block Grant funds, and other mandatory spending based on local plans.

High-quality technical assistance would be provided to help selected communities develop plans and to set up measurement systems that integrate data across a variety of sources. Additional federal dollars would be provided for evaluations. While the initial plan would be for a multiyear period, it could be adjusted annually as the community learns what works and what doesn’t. The plan could include additional incentive funding for communities to participate.

In implementing this proposal, the federal government would need to develop carefully tailored guidance and guardrails to ensure that communities selected for this initiative use this additional flexibility to enhance rather than reduce services for families most in need. Regulations will need to prevent the practice known as “creaming,” whereby providers or local governments can artificially produce better outcomes by serving lower-risk populations. The antidote to creaming is the use of good, comprehensive data to clearly identify the high-risk individuals a program aims to serve, and requirements that communities selected for this initiative continue to robustly serve those individuals. Finally, communities selected for “zone” status would need to first meet a set of minimum requirements, demonstrating a commitment to successfully using data to measure and track key outcomes.

Because practice pilots are often slow to become widespread policy even if they are successful, we propose that scaling potential be built into the initial design of the program. Therefore, if a zone shows promise after the first two years of implementation, additional zones within the state can be added and additional technical assistance, investment, and evaluation funding would be provided. The proposal would include strong incentives for governors to scale efforts that come near to achieving—or exceed—the initial outcomes targets.

Finally, the initiative would include funding to support staff, evaluations, technical assistance, data system modernization and integration, and other types of “outcomes infrastructure” essential to make outcomes-based innovation viable and sustainable.

33. REFRAME THE “FUTURE OF WORK” DISCUSSION TO INCLUDE TALENT IN THE SOCIAL SECTOR.

Ensure a talent pipeline for the social sector to fill shortages, support quality and scale, and reflect the communities served.

The people who work for and lead our social-sector programs are the key to their success, both in and outside of government. We know from experience just how important hiring and retaining talent is at every level. We also know that hiring people who have lived experience in the communities served or with the issue we are seeking to address is essential. Many America Forward Coalition organizations point to hiring and retaining talent as a major obstacle to growth.

The people who work for and lead our social-sector programs are the key to their success, both in and outside of government. We know from experience just how important hiring and retaining talent is at every level. We also know that hiring people who have lived experience in the communities served or with the issue we are seeking to address is essential. Many America Forward Coalition organizations point to hiring and retaining talent as a major obstacle to growth.

To date, discussion of the “future of work” has centered on the role of technology displacing workers in the business sector. We call for expanding this conversation to encompass other workforce trends and challenges, namely the importance of preparing and recruiting social-sector talent—the people who will solve the major human service and education challenges of our day, as well as educate the technology workforce of the future and retrain the workers displaced through technology.

This is no small feat. Nonprofits account for roughly one in 10 jobs in the private workforce in the United States, with total employees numbering 12.3 million in 2016. Over the decade since 2007, nonprofit jobs grew almost four times faster than for-profit ones. For the first time, nonprofit employment now equals manufacturing. Retail trade and accommodation and food services are the only American industries that employ more people than nonprofits. Add public-sector jobs, which include most teachers, police officers, and nurses, as well as government agency employees, and the total numbers 22 million.

As with most segments of the workforce, the federal government will be particularly hard hit by the retirement of the baby boomer population. The Congressional Research Service indicates 52% of public workers are aged 45-64 compared to 42% in the private sector. The aging of the federal workforce reflects long-term retention, which can be a good thing. But it also means that individuals are not moving across sectors, bringing new knowledge with them, and that young people are not able to enter the field, bringing their lived experience, new skills, and tech savvy to government.

We propose four strategies to address the talent challenge in the social sector, including government: universal national service, free college for students who commit to work in shortage areas, midcareer talent teams, and support for “encore” careers.

1. Scale universal national service for young adults.

National service is a proven strategy to develop talent from the ground up—developing young leaders from all backgrounds, including underserved communities, and drawing top talent into fields in need of innovation. Scaling national service and deepening the career development outcomes of these programs are key to reshaping the social sector for the future.

Corps members build both civic and workforce skills that can be useful in either the public or private sector, including for-profit businesses. However, recent research for Service Year Alliance by Burning Glass, comparing the resumes of individuals who have completed a service year with a matched comparison group, revealed distinct patterns that differentiate service year alumni from their peers, both in the careers they forge and in the skills they develop. For example, service year alums go on to complete bachelor’s degrees at higher rates than their peers, are more likely than their peers to work in education and community and social-services occupations, and are more likely than their peers to advertise skills related to leadership and organization. In addition, they appear to advance faster in these fields.

AmeriCorps members play an outsized role supporting the education field. In addition to providing full-time, near-peer corps members to support school success in dozens of high-impact programs, AmeriCorps is a top feeder for both traditional and nontraditional teacher professional preparation programs. Other common paths from service include a variety of nonprofit (50% of VISTA alums work in the nonprofit sector), conservation (12% of park service employees come from the Student Conservation Association), and disaster response (more than half of recent FEMA Corps alums went on to careers in emergency management) careers.

Unfortunately, fewer than 100,000 Americans have the opportunity to engage in a year of civilian national service each year. Strategies to make it a bigger part of a national strategy for the social sector include:

- Scale AmeriCorps and targeting expansion to fields likely to experience labor shortages and communities, incorporating AmeriCorps into social innovation zones and other place-based initiatives.

- Incentivize national service programs to incorporate the ability to earn workplace credentials or postsecondary credit.

- Expand funding for AmeriCorps recruitment and technology solutions to make it easier for corps members to find positions tied to their career goals.

- Increase both AmeriCorps living allowances and Segal education awards, and make them tax-free, to make it easier for low-income people to serve.

2. Provide free college to students eligible for financial aid who commit to a term of employment in shortage social-sector fields or innovation zones and other underserved communities.

Providing free college in the form of scholarships or loan forgiveness to students who agree to take jobs in underserved communities and shortage fields solves two problems: It provides debt-free college access while drawing and retaining talent, including people from the communities served, into high-need high-turnover fields such as early childhood teaching, social work, and technology-related social-sector work.

This program can be modeled on the National Health Service Corps, a federal recruitment and retention program that reduces health workforce shortages in underserved areas by providing scholarships or loan repayment in exchange for a two-year term of service. Available data indicate that four in 10 remain at their service site, and another four in 10 practice in an underserved area one year after their service commitment has ended. A FY 2012 study found that more than half remain in an underserved area 10 years after completing their service.

This program can be modeled on the National Health Service Corps, a federal recruitment and retention program that reduces health workforce shortages in underserved areas by providing scholarships or loan repayment in exchange for a two-year term of service. Available data indicate that four in 10 remain at their service site, and another four in 10 practice in an underserved area one year after their service commitment has ended. A FY 2012 study found that more than half remain in an underserved area 10 years after completing their service.

3. Develop midcareer talent.

To make our public programs more outcomes-driven, we must open up the constricted public-sector talent pipeline to entrepreneurs, innovators, disrupters, and those with relevant lived experience and proximity to major social challenges. We need fresh thinking and innovative approaches from experienced and emerging leaders capable of orchestrating shifts across large organizations.

Programs with bipartisan support like the U.S. Digital Service; nonprofit programs including FUSE, Code for America, Third Sector, and Foster America; and secondment programs administered by the World Bank and Johnson & Johnson all point to the systems change potential of recruiting and training midcareer emerging leaders from outside government for temporary public-sector fellowships. For example, the Government Performance Lab embeds fellows in state and local government agencies. By providing the agencies with the ability to use integrated data to measure and scale what works and adjust what doesn’t, the Lab has successfully used data to encourage performance management and help move the dial on outcomes in 96 projects spread across 67 jurisdictions in 31 states. In Rhode Island, for instance, a team of fellows dug into the data and adjusted a set of state contracts to reform and improve the state’s child welfare system. As a result, Rhode Island increased its foster home capacity by 66%, reduced group home placements by 23%, increased preventive services by 180%, and drove down nearly threefold the share of families necessitating a state intervention after receiving preventive services.

Building off these and other proof points, including Intergovernmental Personnel Act and professional exchange programs that have shown promise, we should build a new talent pipeline into the public sector. A new pilot program of competitively selected midcareer leadership fellows could provide the needed expertise and expose individuals with experience in other sectors to opportunities within government. The pilot would focus on individuals with technology, STEM, procurement and acquisition, human resources, and managerial expertise, all areas in particular where the current public-sector workforce could benefit from a talent infusion.

The pilot would ramp up over time, eventually including 500 full-time fellows per year. Fellows would serve across federal, state, and local agencies to help break down conventional silos, improve information flows, and catalyze systems change. Although fellows would report to upper management and leadership within their agencies, they would also be clustered as a diffuse network, with the goal of moving the needle on a few key measurable outcomes, transcending the existing organizational hierarchy.

The initiative would recruit broadly and energetically, casting a wide net across many sectors. Fellows would have robust support, technical assistance, and training designed to maximize their effectiveness within the public sector; shift agency cultures; and catalyze broader positive systems change across the agencies in which they serve.

While components of this vision could be achieved via an Office of Management and Budget and Office of Personnel Management executive order, bipartisan legislation amending the National and Community Service Act would help provide the necessary funding and authorities.

4. Support “encore” careers.

Today there are more people in the United States over 50 than there are under 18. By 2035, 140 million Americans, more than one in three, will be over 50. With decades of productivity ahead, adults over 50 are a growing and renewable resource for the nation. Recent research examined the life goals and values of individuals aged 50-92 and found strong support for helping others in later life. Unfortunately, many Americans who are eager for meaningful work later in life don’t have a pathway to do so.

Service experiences provide a powerful way to transition into a new stage of work, including from business to the social sector. We support the new Early Childhood Legacy Corps program, proposed by Encore.org, which facilitates these transitions through part-time, modestly stipended service, and engages older Americans in early childhood care where there is an urgent need. By tapping into funds currently available to them governors can mobilize an underutilized source of talent—older Americans—to provide needed capacity to early childhood settings by providing a modest stipend to those making significant commitments to serve in this way. By leveraging intergenerational solutions around early childhood needs, government leaders will have the ability to knit together communities and generations, and to mobilize an underutilized talent source.

34. SCALE HIGH-IMPACT ORGANIZATIONS.

Provide growth capital to help grow high-impact organizations that are central to helping government work better, enabling providers to achieve greater impact and deliver services directly.

1. Create a community-solutions tax credit.

The Social Innovation Fund (SIF), discontinued in 2017, invested in evidence-based community solutions in 46 states and Washington, DC. Private and local funders nearly tripled the federal investment, channeling over $700 million to expand programs that work. These investments provided critical support to nearly 500 nonprofit organizations across the country—helping grow effective programs and develop innovative approaches to some of the most pressing challenges in economic opportunity, healthy futures, and youth development. The SIF grew into a social impact incubator within the federal government, creating public-private partnerships that deliver high-impact, community-based solutions that work.

Building on this experience, a “community solutions tax credit” would further recognize the asset represented by private-sector funders across the country that have developed highly sophisticated systems for identifying promising solutions to community problems. These funders would compete for the opportunity to issue a specific amount of tax credits to donors who support evidence-based high-impact initiatives. The use of a tax credit offers greater potential for scale and sustainability, creates less bureaucracy, and puts the decisions for investment in the hands of experienced private-sector funders instead of the government.

2. Create new tiered-evidence and outcomes funds at both the federal and state levels, launch new outcomes-based projects at the state level, and expand and update a recently enacted federal outcomes fund at the U.S. Treasury.

- Tiered-evidence funds. Over the past several years, America Forward has worked with other leaders in the outcomes movement to create new tiered-evidence innovation funds. “Tiered evidence” refers to a practice of providing larger grants to programs with higher levels of evidence to enable replication of approaches that have proven effective in one jurisdiction, while providing smaller grants to pilot, test, and rigorously evaluate innovative new approaches. To date, tiered-evidence funds have been authorized in the areas of K-12 education, teen pregnancy prevention, and global poverty reduction. In addition, bipartisan legislators have introduced legislation, supported by America Forward, to create a Fund for Innovation and Success in Higher Education Act (FINISH Act), which would create a new tiered-evidence fund to improve graduation rates and boost the attainment of post-secondary credentials for at-risk students. Other potential areas for tiered-evidence innovation funds include early childhood, workforce development, homelessness, criminal justice, and health care.The advent of tiered-evidence innovation funds suggests a new vision for government, where taxpayer dollars fund outcomes over inputs, are explicitly linked to impact, and help communities scale approaches that work. This approach can be transformational. As long as agencies pay based on inputs, they see high upfront costs for the most effective approaches, which often happen to be the most intensive, and therefore the most expensive. By shifting to an outcomes-based approach, with funding tied explicitly to results, the very factors that previously inhibited public sector take-up of these approaches could accelerate it. Of course, it’s also essential that we avoid creating an inflexible recipe, constantly replicating exactly something that worked sometime, somewhere. To be effective, this approach must dynamically incorporate continuous learning, adapting to new information and the tailored needs of communities.

- Outcomes Funds. In order to build proof points and success stories in communities across America, states should create new “outcomes funds,” raising supplementary capital from philanthropy where necessary, and allowing local government agencies and providers to access the funding over time based on measurable results. With safeguards and incentives to ensure outcomes funds pay for services for the most under-resourced people (without allowing providers to “game” the system by only serving lower-risk individuals and families), this approach could drive dollars to effective services with lower transaction costs and less complexity than many of the first generation of Pay for Success projects. Governors could appropriate new funding for such approaches or harness existing federal funding streams. Tapping and combining a portion of their state reserves for federal programs such as WIOA, Perkins V, and the Child Care and Development Block Grant would be a good place to start.

- Social Impact Partnership to Pay for Results Act (SIPPRA). SIPPRA is a $100 million federal outcomes fund housed at the Department of Treasury, recently enacted and funded with substantial advocacy from the America Forward Coalition. While the first cohort of SIPPRA projects represents real progress, many view the notice of funding released by the Treasury in early 2019 as overemphasizing cost-savings, underemphasizing innovation and value for families and the nation, and overly focused on Pay for Success financing, at the exclusion of other components of Pay for Success. Congress should infuse SIPPRA with a new tranche of funding, exponentially increase funding available for feasibility work, and make this new tranche of funding eligible to fund other more innovative approaches.

3. Provide bonus payments to nonprofit providers that achieve outcomes.

All too often, budget-constrained agencies fail to pay nonprofit providers what their services actually cost. Of equal concern, rules and regulations frequently sharply limit how nonprofits can use these dollars, impacting their ability to grow and scale. This is antithetical to what venture philanthropies like New Profit have repeatedly demonstrated over the past two decades: that social entrepreneurs doing good work need unrestricted growth capital to scale.

We propose a new approach that will help address both these challenges. Across selected major formula funding streams and grants such as TANF; the Social Services Block Grant; the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act; and the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting program, the federal government should offer modest bonus payments of 10% beyond base contracts for nonprofit providers that exceed certain target outcomes based on independently validated administrative data, with safeguards to make sure harder-to-serve individuals are not excluded in order to inflate outcomes. Critically, nonprofits could use these bonus payments in any way, so long as they were program- and mission-related, creating a new source of public-sector unrestricted growth capital based on positive impact.

This proposal would help enable a new wave of outcomes-based projects. More important, it would create healthy external pressure from local providers for state and local governments to improve their data systems, and to help catalyze scalable outcomes-based contracting by creating incentives for both providers and local governments to do more of it.

35. EXPECT MORE FROM THE COMPANIES THAT DO BUSINESS WITH THE GOVERNMENT.

As the corporation social responsibility (CSR) movement grows, promote greater transparency regarding the companies that government does business with by making contractors and their CSR records easily accessible.

The modern corporate responsibility movement started in the 1990s and has grown and matured over the decades. While initial efforts were a response to stakeholder pressure and market positioning, today it is widely accepted that companies should be accountable for their environmental, social, and governance practices. Not only are millennials demanding higher standards from the businesses they support and work for, but also research documents the link between good CSR, financial performance, and sustainability. Today, CSR extends beyond the early focus on environmental practices, worker exploitation, philanthropy, and employee volunteering, to encompass a much broader range of practices, including pay; sexual harassment; data privacy; health and safety; supply chain accountability; and diversity, equity, and inclusion of a broader set of underrepresented people.

To push companies to do more without the worry of shareholder backlash, an order should require all contractors to make their CSR records and policies public. While we would not at this time support requiring a specific set of CSR practices, a policy of this sort would build awareness, expand data, increase transparency, discourage contracting with companies with poor CSR track records, and enable future analysis of the relationship of CSR practices to performance.

CONCLUSION

We can’t get the results we need, and that all people deserve, without a government that works for everyone. That government is within our reach—if we have the courage as a country to listen to and lift up the voices of all people; make the hard decisions to support what works based on data, not political expediency; and expect more from the companies, policymakers, and citizens that have the power to make the difference.